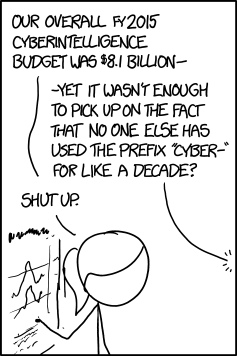

Ovenstående XKCD-stripe spejler mange internetmenneskers hovedrysten over statens og det sikkerhedsindustrielle kompleks' brug af præfikset cyber- om alting på internettet. De er ude af touch. Det er gammeldags. Sådan tænker vel de fleste - men jeg tror man går galt i byen, hvis det er det man tror det handler om.

Cyber- har vi fra cyberspace. For de fleste, er det et ord, der kom fra William Gibson og hans - ja, undskyld - cyberspacetrilogi, med gennembruddet Neuromancer som den vigtigste roman.

Men præfikset er ældre. Kilden til ordet er Norbert Wieners kunstord cybernetics - om den nye videnskab om feedback og kontrol han opfandt under og lige efter 2. verdenskrig. Order kommer fra græsk - kybernetes, som betyder styrmand - eller allerede hos de gamle grækere også metaforisk: Den der styrer. En leder.

Kontrol

Wieners kybernetik - og ordet cyber - handler altså meget præcist om én ting: Kontrol. Vores begreb om information - også affødt af 'the cybernetic turn' efter krigen er på sin vis en biomstændighed ved udviklingen af kontrol.

Kybernetikkens og informationens allerførste usecase var våbenstyringssystemer. Automatiske sigteapparater til hærens og flådens kanoner. Informationen skulle bruges til at etablere kontrol. Informationen var aldrig pointen, kontrollen var.

Og ordet cybers rod har aldrig forladt internettet, og har på intet tidspunkt været væk. At NSA og hele det statslige sikkerhedsapparat betitler alt internet med cyber, handler om at missionen ikke på noget tidspunkt har været væk - ikke om at de sidder fast tilbage i 80erne.

Selv ikke i Gibsons romaner er kontrol og magt på noget tidspunkt væk. Gibsons hovedpersoner er altid i kløerne på - eller agenter for - tågede stærkere magter; sådan lidt ligesom i klassisk græsk drama, hvor Odysseus og alle de andres historier i sidste ende er givet og berammet af guderne. Det er simpelthen urformen på Gibsons plots, fra Neuromancer over Pattern Recognitions til The Peripheral. Uafhængighed er en dyrt vundet luksus for de allerrigeste - og selv den har grænser.

Så grin bare af cyber- det ene og cyber- det andet. The joke's on you.

(Hvis man vil læse mere om informationens historie og computerens og nettets ditto så kan jeg kun varmt anbefale James Gleicks 'The Information' - eller man kan læse George Dysons 'Turings Cathedral', som også er god. Læser man begge vil man opleve en vis deja vu, men de er begge gode og forskellige nok til at være besværet værd)

Hvis du bor i hovedstadsområdet, så kan du forresten tage på vinduesudflugt til Det Nye Arbejdsmarked ved at tage ud og se DR Vejrets gadeplansstudier i DR Byen. Indenfor er der ikke nogen, eller, der sidder en skærmtrold og kigger på en skærm, måske ser han sidste udsendelse igennem eller også laver han noget helt andet. I selve studiet er der ikke nogen. Kameraerne er nemlig fuldt robotiserede og har ikke brug for mennesker omkring sig. Således er mennesket i maskinen i virkeligheden bare blevet det forarbejdede produkt; produktet selv laves af maskinerne.

Vi flytter os fra en verden der er kultur, der laver teknologi, til en verden der er kultur, der betjener teknologi, der laver teknologi. Vi bliver siddende i vores jolle ovenpå, men det teknologiske farvand under os bliver dybere og dybere.

Antikythera-mekanismen blev fundet på 60 m vand, den 17. maj 1902, på et græsk oldtidsvrag ved øen Antikythera, nordøst for Kreta. Den lignede en sten, men en dykker ved skibsvraget lagde mærke til at der tilsyneladende var tandhjul indlejret i den. Mekanismen er et kompliceret værk af med mere end 30 tandhjul. En kompleksitet, der er på niveau med ure fra 1900-tallet, ikke som de maskiner man ellers kendte fra oldtiden. Mekanismen repræsenterer simpelthen en viden, man ikke forestillede sig oldtiden havde, før man fandt den - og af samme grund gik der mange år før man overhovedet kom igang med gode gæt på hvad det overhovedet er maskinen kan. Idag mener man at mekanismen kan beregne positionen af forskellige himmellegemer med høj præcision, og ser den som verdens ældste kendte analoge computer - ikke bare som et overraskende fortidsur.

Der har været masser af bud på rekonstruktioner af maskinen, så man kan komme til at se den i funktion, og på den måde finde ud af hvad det egentlig er computeren beregner. Men det er altså ikke mange oldtidsfund, der er så gådefulde. Normalt er gåden mere spørgsmålet om de kulturelle vaner omkring tingenes, ikke konkret funktion. Den meste af den viden vi mangler, og kan søge, om oldtiden er kulturel, ikke teknologisk, og særlig i den græske oldtid - som havde en rig skriftkultur - er det sproget vi har vores viden fra, og sproget vi gemmer vores viden i. Sådan har det været i nogle tusinde år. Det er sproget, der har gjort os kloge. Sproget har syntetiseret kulturen rundt om os, og det er sproget der har fanget vores viden. I den forstand er Antikythera-mekanismen en spektakulær undtagelse. Den er designet, men ingen af os kender designet. Vi kender kun dets konsekvenser i form.

Når fremtiden finder vores egen tid frem fra en ny havbund, vil det se en del anderledes ud, for jo længere ud chokbølgen fra informationseksplosionen når, jo mere bliver vores viden aflejret i teknologiske artefakter, ikke i kulturelle artifakter.

Vi bliver hver dag lidt mere cyborgs - menneske/maskiner. Vi får mere og mere informationsteknologisk svømmehud mellem fingrene til at padle runde i verden med. I form af apps og mere og mere web, og mere og mere viden vi altid kan tilkalde fra skyen. Den teknik/kultur-mixede fremtid er i færd med at afsløre sig som en hvor viden ikke så meget er noget vi har som noget vi sørger for at de maskiner vi omgiver os med lagrer på en eller anden måde;. Det bliver mere og mere broget hvad det egentlig betyder at vide noget. Hvad er viden overhovedet?

I sin nye bog, Too Big To Know, gør David Weinberger os klart hvor almindelige de nye vidensformer er ved at blive, og hvor forskelligartede de er.

Hvad var de gamle vidensformer, da? I en naiv, idealistisk, fremstilling af viden, som den var de de gode gamle dage, så studerede vore forfædre verden i laboratoriet, eller ved at gå ud og se sig om i den. Fra det studium, tog man sine konklusioner om hvordanverden er. Konklusionerne bragte man så i sammenhæng, og skrev sammen til længere traktater, hvor man satte verden fagligt på plads. Arketypen for den slags viden er måske fysikken og matematikken - hvor års studier endelig fører til det ultimative destillat, nemlig de grundsætninger, der er verdens principper. De arketypiske bogværker fra den videnskultur er de store filosofiske traktater - Platons værker fra Antikythera-mekanismes oldtid, f.eks. Eller de store naturvidenskabelige værker. Newton skrev Principia, og formulerede sin 1., 2. og 3. lov - og så er billiardkugleuniverset, altså verden uden elektricitet, lys og kernekraft, på plads. Naturlovene er verdens indre sammenhæng, og resten er bare historier vi fortæller om den verden, der har disse egenskaber.

Springer man fra oplysningstidens gentlemanforskere til idag, konstaterer man at vores viden forlængst har overhalet vores sproglige kapacitet. Eller rettere: De bøger - altså fortællinger - vi har krystalliseret vores viden ud i, er blevet erstattet af mere effektive måder at fange viden på. Samtidig med at mediet for vores viden er skiftet fra det fortællende sprog, til andre og nye former, så har målsætningen med vores videnproduktion forandret sig. Hvis nu man ikke længere skal producere en bog, skal man så overhovedet bruge den fortællende røde tråd, det gjorde bogen læsbar?

Hvilken værdi har syntesen, nær dens primære hensigt - at skabe en linje gennem et stort korpus af viden - ikke længere er gyldig?

Hvis man skriver software idag, så er der en god chance for at man dagligt støder på websitet Stack Overflow. Stack Overflow har vendt genren "computerbog" på hovedet. Sitet fanger nu en overordentlig stor del af den viden, man har brug for i sin softwareudviklende hverdag, uden store korpus og 2 års grundkursus per emne, simpelthen som en massiv database af spørgsmål, med detaljerede svar, der peger helt præcist lige derhen i det samlede tekniske bibliotek, der løser spørgerens opgave. Hvis man er skolet på den gamle måde, og tænker helhedsorienteret - eller endda heroisk i softwareudviklerens apoteose(*), så lyder det jo helt forfærdeligt med den slags reaktiv problemløsning, men i en travl hverdag er det fantastisk effektivt til at omgå forhindringer.

Stack Overflow er den naturlige konsekvens af den videnseksplosion feltet oplever. Omkostningerne ved at vedligeholde sit eget tekniske bibliotek, og sin evne til at bruge det, er simpelthen for høje, og adgangen til ressourcer som Stack Overflow hjælper os med at undgå den omkostning. Stack Overflow er for programmøren hvad Wikipedia er for den stileskrivende gymnasieelev, på godt og ondt. En mulighed for at gå uden om det enorme besvær - at erobre sit eget suveræne overblik.

Spørgsmåler er så: Ved jeg overhovedet det jeg finder svaret på, på Stack Overflow? Puristen fra fortiden svarer klart nej. Skoleeleven og den travle og trætte programmør er tilbøjelig til et pragmatisk ja, men pointen her er, at puristen har mere ret. Det er samfundet på Stack Overflow. der er intellektet her. Vi andre bruger det bare.

Lad os tage den påstand længere ud, med et eksempel mere.

Filmsitet Netflix har gennem de sidste par år haft en konkurrence kørende om at forbedre sitets mulighed for at foreslå nye film at leje til sitets brugere, baseret på de film de iøvrigt kan lide.

Den måde man løser den type opgaver på, ser forenklet sådan her ud. Man laver en model af hvordan brugere rater film. I den propper man de ting man ved om brugeren - hvad han ellers har ratet hvordan - Modellen vil som regel afhænge af en hel masse parametre, og man bruger så data fra Netflix til at tune parametrene, så man får den mest troværdige nye rating.

rating = Model(film, bruger, parametre)

Det interessante for os er, at der ikke egentlig er så meget information i modellen - det er tit og ofte de samme slags modeller man bruger til alt muligt forskelligt fra film-ratings til fabriksoptimering til videogenkendelse. Kunsten består i at optimere modellens parametre så der kommer de helt rigtige ratings ud.

Når nu modellen kan betyde hvad som helst og ikke handler specifikt om film overhovedet, men bare er en mønstergenkender bliver det modelparametrene, der er den egentlige viden, ikke modellen. Og parametrene er altså ikke formuleret som en smuk historie om Netflix-brugeren, og hvad han eller hun er for en, og hvorfor de derfor foretrækker det ene eller andet. Historien er væk - der er kun den rene viden - "hvad foretrækker han?" tilbage.

Hvis det var nemt at påstå at vi skam stadig ved det vi ved, vi organiserer det bare anderledes, i Stack Overflow-eksemplet, så skulle Netflix-eksemplet gerne gøre det lidt sværere.

I den sidste uges tid dukkede endnu et illustrativt eksempel op i min linkstrøm. Der har været meget opmærksomhed omkring Stuxnet-ormen - et formodet israelsk cyberangreb på de fabrikker i Iran der beriger Uran til atombombeproduktion . Som Antikythera-mekanismen, er ormen et umådeligt sofistikeret værktøj af ukendt oprindelse. Eksperter har kunnet matche kodens funktion med visse helt bestemte Siemens industrikontrolsystemer, som det var kendt Iranerne brugte på deres atomfabrik.

Stuxnet-ormen har en slægtning, Duqu. Den angriber den samme type systemer, men de viruseksperter, der analyserer den, er stødt på det problem i analysen, at dele af den er skrevet i et sprog de ikke kan regne ud hvad er. Det relevante her er at man altså ikke alene - som med Stuxnet - ikke kender virussens design. Man ved end ikke hvilket værktøj den er designet med.

Den form for viden - og uviden - bliver der mere og mere af. Tilbage i 1970, da de første CPUer til de første mikrocomputere blev designet, kunne man lave dem i hånden. I en moderne CPU er der tæt ved en milliard enheder. Ingen designer kan redegøre for den præcise placering af alle dem.

Den form for maskine kan kun designes af andre maskiner - et menneske, der ikke allerede formulerer sig gennem andre maskiner, har ikke en chance for at bygge den slags.

I tilfældet Duqu er det formodentlig helt med vilje at man har valgt et eksotisk designværktøj for at gøre det sværere for os andre at følge med, men Duqus ukendte kildekode, og Netflix' tusindvis af parametre er i virkeligheden eksempler på det samme. Den kode Duqu-forskerne kigger på, er dataoutput fra andre stykker kode.

Den meget komplicerede maskine, er kun med allerbedste vilje designet af et menneske. I en ikke alt for fjern fremtid vil mere og mere af den viden der omgiver os være designet måske af mennesker, men af mennesker, der brugte maskiner, der var designet af maskiner, der var designet af maskiner, der var designet af maskiner. Og, hvad der er lige så interessant, Duqu og Stuxnet er ekstrasvære at forstå, fordi de handler så specifikt om ét eneste system i Iran, som de er designet til at angribe. Duqu og Stuxnet er superavancerede væsener, der læner sig op af en global infrastruktur og er bygget til at mønstergenkende en eneste fabrik i Iran og ødelægge den. For alle os andre, der ikke bliver genkendt, gør maskinerne simpelthen ingenting. Højt specialiseret viden, synlig overalt på kloden, men lavet af maskiner vi ikke kender, til maskiner vi ikke kender.

Den front der skaber fremtiden bliver større og større. Det betyder for os, at vi mere og mere ser løsninger der tager sig specialiserede ud, og som ikke primært er lagret til os som kultur vi kan forstå, men som overvældende mængder af data eller algoritmer - som i virkeligheden er præcis det samme.

Verden, som vi ser den, vil i stigende grad tage sig ud som Duqu-ormen eller Antikythera-mekanismen eller Netflix-algoritmen, der i virkeligheden er mere data end algoritme.

Vi flytter os fra en verden der er kultur, der laver teknologi, til en verden der er kultur, der betjener teknologi, der laver teknologi. Vi bliver siddende i vores jolle ovenpå, men det teknologiske farvand under os bliver dybere og dybere.

Here's an extremely interesting slide deck(pdf) on the opportunities in chip design, if we allow a little more of the physical characteristics of the chips to play a role in the programming interface. Turns out symbolic simulation of floating point math (i.e. real numbers) is extremely compute expensive when you consider that the physics is naturally 'solving' these equations all the time, just by being, you know, real physical entities.

The 'only' cost of a projected 10000x improvement in efficiency is a 1% increase in error rate, but if you change the algorithms to suppose a certain level of error - a natural notion in the realm of learning algorithms and AI-techniques - that's not really a problem at all.

The reason this is important, is, that we're moving from symbolic computing to pattern matching, and pattern matching, machine learning, AI and similar types of computation all happens in the real domain. A 10000x advance from more appropriate software buys about 13 applications of Moore's Law - something like 20 years of hardware development we could leapfrog past.

A few years back I wrote down a guess - completely unhampered by statistics or facts - that in 10-15 years 90%-95% of all computation would be pattern matching - and I stand by that guess, in fact I'd like to strengthen it: I think, asymptotically, all computation in the future will be pattern matching. This also ties into the industrial tendency I was talking about in the previous post. Increasingly, filtering is where the value of computation comes from, and that makes it highly plausible we'll see specialized chips with 10000x optimizations for pattern matching. Would Apple need to ship any of Siri's speech comprehension to the cloud if the iPhone was 10000x more capable?

Postscript: Through odd circumstances I chanced on this link the exact same day I chanced by this report(pdf) on practical robotics. I'll quote a little from the section in that called 'Let The Physics Do The Walking':

Mechanical logic may be utilized far more often in Nature than we would at first like to admit. In fact, mechanical logic may be used for more in our own robots than we realize[...] Explicit software we originally envisioned to be essential was unnecessary.

Genghis [a robot] provides a further lesson of physics in action. One of the main reason he works at all is because he is small. If he was a large robot and put his foot in a crack and then torqued his body over, he would break. Larger walking machines usually get around this problem by carefully scanning the surface and thinking about where to pyt their feet. However, Genghis just scrabbles and makes forward progress more through persistence than any explicit mechanism. He doesn't need to build models of the surface over which he walks and he doesn't think about trying to put his last foot on the same free spot an earlier foot was placed.

Sometimes general computing is just too general for it's own good.

Once in a while it's worth wondering what profound changes we're in for in the next decade if any. With that in mind, what's going to be the most common prosthetic in 2020 that none of us have today? Phones and smartphones are out of the running - we already all have those. Tablets are almost out of the running - or they would probably be the answer.

Let's exclude them - then what is it going to be? Or is the question wrong - like asking "what will be the most popular programming language in the home in 1990" in 1978? Will evolution be elsewhere? Won't technology be evolving in the prosthetic space at all?

My professional bet is on biohacks, but that might just be a little too science fictiony for a while to come. Other than that a swarm of chips around the phone seems likely to me. iPhone ready jackets and watches and glasses and pockets. 2020 might be too close for that. It might take another 5-10 years.

It never hurts to repeat a good point: The silos we're all moving into now can all be leapfrogged. The second the silos aren't simplifying, but instead hampering, innovation and expression, they'll start to loose. Maybe they are beginning to loose right now. Google seems intent - in everything but search - to make sure the silo is just a convenience, not in-circumventable fact.

In other silos-are-breaking news: The T-mobile/Sidekick catastrophe, and we could end up on a modern, open, federated communications platform instead of a silo, and a silo so stressed by growth, that it's really hard to get data out of it that is more than 2-3 days old.

Googler's current and ex- are also still working on moving people to open social networks. Open social maybe wasn't really the sweet spot that one hoped for, but new projects are trying to get there. One wonders along the way if Twitter is moving to a Mozilla business model? Free to use, we just sell the behaviour of our users.

Facebook is going to have move as well - just because of the things you can do with data you can get at. What I'm trying to say, really, is that if you plan to be doing something interesting in two years, I would personally bet on desilofication over "better, but closed" data, just on general principle of cycles.

By which I mean, which awesome features do I have on my phone - and by metonymic extension - in my fingers, because of the software running on my Android phone.

Listed here in order of discovery -

- Transparency The communication platform has ceased to be relevant. The Android does them all; IM, email, texting, Skype. I never have to reveal my state and location to counterparties and they never have to worry if I'm near communicaton mode. X

- Geography Obvious, but secondary to transparency. Getting lost is locking yourself out of your apartment without keys. It can happen, but it takes bad luck.

- Star power I don't use the Skymap app that much - but it's a superpower of such obvious flair that it goes high on the list.

- Radiance My G1 works fine as a makeshift Wi-Fi access point using aNetShare. Where I am, the world is.

- Memory Lest I forget. Recording context to camera is very powerful.

- Sound All the music of the world is with me all the time with the Spotify app. I can play music with the piano app.

- Knowledge Sure browsing, ordering tickets and so on is nice to have all the time. However, the mobile situation does not lend itself necessarily to actually using this super power

The real time transcripts of the Apollo 11 mission are proving to be an even better experience than I had hoped. After making the site I found out about all the other sites doing similar things - but they're either leaving out some of the ugly detail - losing the realism - or doing "educational CD-ROM"-like material around it - losing the forced focus of just people in real time. By a happy coincidence, I haven't really found the experience Morten and I did anywhere else.

Growing up I was a full on bookish space child. Did fake meteor craters dropping stuff into pans filled with flour. Me and my brother had a rocket-on-a-string setup made of LEGO for a long time where we staged launches to the moon/ceiling. I read every book I could find with space in it. Reconstructed the scale of things in space in the garden. But the funny thing is that none of that gave any kind of experience remotely like this reenactment. The rigidity, for lack of a better word, of the experience; just having to wait for things to occur, and not skipping the tedious parts mixed in with the exciting bits, really makes the scope of the mission come to life.

Somehow the garden space reconstructions didn't sell the baffling size of space as well as a 3 day cruise to cover one light second of space at 5000 km/h.

It's shocking how manual everything is. Presumably there's telemetry to Apollo - but numbers are constantly being read manually back and forth over the radio to check that the capsule idea of what the status is matches that on the ground - an interface design lesson there, btw. Procedures and manuals for proper operation are being rewritten on the fly dictated over the air.

Jeg har kigget en smule på fremtidsproblemet vand her på det sidste. Det der fik mig til at tænke på vand var et sci-fi koncept som tegningen ovenfor: Omvendte floder, store pipelines med havvand, der på ruten ind i de mere og mere vandsultne kontinenter destilleres til menneskebrug og til landbrug.

Hvor realistisk er sådan en plan? Det er lidt besværligt at få styr på nogen gode vandtal, men til sidst fandt jeg nogen et af de steder hvor problemet allerede er akut, nemlig Israel

Her bygger man for tiden en serie enorme afsaltningssanlæg der producerer 100 mio. kubikmeter drikkevand per år.

Israels totale tilgængelige vandressource før anlæggene er 2000 mio kubikmeter vand per år - egentlig alt for lidt til den befolkning der bor i området.

Et anlæg der producerer 100 mio kubikmeter, leverer altså 5% oven i den mængde. Man skal altså "bare" bygge 20 af dem for at have en fuld kunstig forsyning - incl. vand til et landbrug, der er nettoeksportør af fødevarer.

Hvor meget energi går der til at producere drikkevand? Hvis man skal gøre det selv uden smart udstyr så må man jo dampe vandet af og kondensere det igen.

Det er meget energikrævende. Det går en kalorie til at varme et gram vand en grad, her skal vi op til kogepunktet, og så også tilføre fordampningsvarmen - ca 5 gange så meget energi som opvarmningen fra 0 til 100.

I de højeffektive afsaltningsanlæg kan man ved at bruge filtrering under højtryk og genanvende den energi man hælder ind komme ned på at bruge 4 kalorier per gram vand, altså energi der svarer til blot at varme vandet fire grader, eller ca. 150 gange mindre end naiv fordampning.

Regnet om til den effekt der kræves til et anlæg i 100 mio kubikmeterklassen er det kun 55MW effekt der forgår. Under en tiendedel af hvad Avedøreværket producerer. Nogenlunde hvad man ville få ud af vindmølleparken i Københavns havn, hvis ellers den producerede på topkapacitet døgnet rundt.

Pointen ved de lidt kedelige omregninger er, at det faktisk lader sig gøre. Man skal ikke æde hele landskabet op med vindmøller, eller bygge 40 kraftværker, for at producere kunstigt vand nok til en hel nation. Et Avedøreværk eller to og 20 destillationsanlæg forsyner et land, hvor der bor omkring 10 mio mennesker.

Hvad angår prisen: Det israelske anlæg sælger vandet til ca en halv dollar per kubikmeter - en pris der dog sikkert varierer en del med prisen på energi. I København koster en kubikmeter vand for en husstand lidt over 40 kr.

En kunstig Jordanflod kunne man altså faktisk godt slippe afsted med at bygge på et par år. Det er ikke en mulighed for de fattigste, men det kan lade sig gøre. Vand til hele Israel for en milliard dollars om året.

Fantastisk trailer for en tydeligvis hjemmelavet italiensk sci-fi film. Ham, der ligner Chewbacca er et fund. Flere fantastiske film hos producenterne.

As a metareflection on the now classic adage that the iPhone is a device from the flying car future we always dreamed of, the speculative device in Bruce Sterlings near-future short story in the most recent Wired Mag has a flash demo that looks conspicuously like the iPhone.

I would be extremely dissappointed if we still have this interface in ten years...

If we look back in ten year increments it goes something like this:

2007: Usable smart phone

1997: Usable laptop - smart phones exist but suck

1987: Usable PC - laptops exist but suck

1977: Personal computers exist but suck

So, hopefully the next decade gives us something completely else. If we use the "it exists now, but it sucks" barometer to gauge the future, what will it be? Arduinish hackable physical objects? A big ass table? eBooks that are cheap and don't suck? Speech recognition we actually want to use?

Note above that I'm not talking about "useful at all" but "generally useful". For each of the generations above, the generation before was heralded as "actually useful" - it's just that there's a long way from actually useful to generally useful.

I'm hoping for "a physical turn" in interfaces.

From Adam Greenfield's del.icio.us stream about "New York Plans Surveillance Veil for Downtown":

"Veil" sounds so gossamer, so shimmeringly innocuous...and then they botch it by keeping "surveillance" in there.

Næsten-sammenhængende links: Gordon Bell har lavet en total optagelse af sig selv og er nu fuldt digital. En use case til hvad man skal bruge den slags til er f.eks. at dokumentere sine dårlige kundeoplevelser - bemærk i den sammenhæng den framragende ironi i at det er en online diskplads løsning der giver den dårlige løsning. Doc Searls kalder i øvrigt den transaktionsorienterede del af sådan et system for VRM - vendor relationship management. Man kan også læse tilføjelser og sammendrag til John Battelles original om datarettigheder.

At the top of the heap and the front of the wave, the ultimate global business traveller has finally uploaded himself permanently to the ephemeral world of hotels, planes and airports. Bruce Sterling with the details.

Perfekt, 2D foto til 3D model som en ny tjeneste online. Når den her bliver integreret med SketchUp så bliver Google Earth for alvor crazy delicious. Fotorealistiske bygningsmodeller på hele jordkloden mand! Det bliver også sjovt at hælde fiktive bygninger i. Tegneserier og den slags. Jeg kan knapt nok vente.

It is in the nature of commoditization that all tradable goods eventually ship in containers. More and more, the goods don't ever leave the containers, in fact. The shipping container quite simply represents goods at maximum commercial entropy. So the commercial, globalized equivalent of heat death is a world simply made out of shipping containers. Yes, of course there's a subculture that is looking forward to this.

The Gartner hype cycle is a fun if shallow model of how new technology find its place in society. The shallowness comes from the idea that the real productivity of the hype does not really live up to the hype. I think that is blatantly wrong and can be proven wrong by checking the numbers. The only reason it feels the way Gartner describes it is, that we adjust to the expectations and aren't as floored by them the second time around as we were during the original hype.

But let's get to the point: The graph above is a model for how we get stuff like the hypecurve. I think in general people are mentally unable to perform exponential extrapolation. What we know how to do is linear extrapolation. This assumption feels natural to me, and I'd be extremely interested in hearing about studies that back this up. Its plausible, if for no other reason then that the world around us is rarely exponential, but usually involves curves following the powers 1 and 2.

The upshot of that, as can be seen from the graph above, is that we tend to drastically overestimate short term gains of a new technology, but at the same time we underestimate long term gains. A really good example of this is is e-commerce. As far as I know e-commerce today is wastly above even the wildest estimates put forward during the first bubble in the late 90s. The only problem with e-commerce is that it took a little longer than expected to get there.

The plateau of productivity, if it exists in reality, has something to do with the exponential ultimately turning into a logistic growth curve instead just from saturation - when saturation is a factor, which isn't always the case.

[UPDATE and Rethink: of course we're never negatively disappointed, or at least we don't waste much time being graciously pleased by overperformance, so the hype is floored at 0 - which gives a nice explanation for the plateau. You'll have to imagine the disappointment as the feeling we have from coming off the sugar rush of the hype. We do in fact go slightly negative just for a while.]

In 10-15 years 90-95% of all computing resources in the world will be used to do pattern recognition.(That's what I believe any way. In terms of CPU resources, most of the stuff on the watchlist is either trivial or really about pattern recognition in one form or another.)

Corollary

The main purpose of almost all data in the world will be to be available as input in a multitude of pattern recognitions.

(That is to say: If you think your current robot/human traffic rate on your website is bad, you ain't seen nothing yet. And this is a good thing. It will happen unless stupid legislators paid by old businesses and scared of the future make it impossible. If we want smarter machines we need to make it as legit and free for a machine to know about a song as it is for you to remember the song.)

Wired rapporterer at grise nu kan, om ikke flyve, så istedet vækkes efter 2 timers dybfrost. Så nu kan man altså snart lave de der rumrejser i dybfrost ud til kanten af solsystemet som sci-fi forfattere altid har drømt om...

It's not perfect, but it's pretty good. Take a look at the Quake projected onto the real world augmented reality demo. This scene (DivX) is very convincing even if there's more work to do...

P.S. Can't wait til the "computer games are dangerous" ambulance chasers get a look at this.

P.P.S. Equally cool 3D modelling against the real world interface. Kind of like an AR version og the Google Earth, Google Sketchup combo...

Dan Kaminski is the maker of the awesome OzymanDNS "ssh over DNS" toolkit that lets alpha geeks use the airport WiFi for free. Lately he's been using DNS to give the world a glimpse of a digital zero-privacy future by tracking the spread of the Sony CD malware throughout the world. He's got lots of pretty pictures.

Oh, and another thing about this whole post human future debate and a future with no need for us: The human brain is remarkable and highly complex, engineerable or not. I fully subscribe to Steve Mann's point of view, as expressed in his notion of humanistic intelligence:

Rather than trying to emulate human intelligence, HI recognizes that the human brain is perhaps the best neural network of its kind, and that there are many new signal processing applications, within the domain of personal technologies, that can make use of this excellent but often overlooked processor.

I've quoted this before but it is worthwhile repeating again.

If the David Weinberger's and the Steve Talbott's of the world will bear with Mann's nerdy reference to the brain as a processor (and yes, I know that this is exactly what you think is a problem), what he is actually saying is that technology and science will rely on our selves and our minds if for no other reason, then because it is the practical thing to do.

In short, the future very much needs us, and it will belong to us.

The Matrix sequel is on it's way and the follow-up to everybody's favourite sci-fi movie of recent years is set to eclipse anything else possible. The story line looks as if it suffers from the usual cases of sequelitis (more monsters, 'return of the eliminated enemy', even more at stake (even if everything was at stake in the first film)) but on a survivable level; the environment (present day, only strangely malleable) is as cool as ever; and finally what's not to like about a sci-fi action movie whose website has a philosophy section.

The saddest thing after a close inspection of the extreme high quality trailer download is that we're still not in computer graphics nirvana. Computer generated images of everyday objects still look computer generated. The first film dealt with this through a lot of physical photography only augmented with effects, but this time around some of the fight scenes have gone full CGI and unfortunately it shows. There's a bad guy smashing the hood of a a car - looking as alive as a barbie doll, and there's Neo himself in 'The Burly Brawl' slugging it out with one hundred Hugo Weaving copies attacking. The most acrobatic shots in the scene - Neo rotating while kicking ass, and a great Weaving explosion tossing all the Hugos through the air look entirely animated. This takes a lot of the coolness out of the scenes. The great thing with the matrix compared to the Star Wars prequels or other effects heavy movies was the super realistic look of the scenes. It's a lot like all the stuff that's wrong with the latest James Bond movie. That too added all kinds of crazy CGI stuff (an invisible car? Get outta here! James bond is a hard drinking, heavy hitting, sex machine - not some alien-tech superhero) and in films whose entire coolness relies on the physical believability of the action that just takes a lot of the cool away.

Needless to say, the believeability of the action in The Matrix is also an important part of the plot, so even though that particular element of surprise is no longer there, the physical believability of the simulation is still an important aspect of life inside The Matrix.

Salon carried a really great story 2 months ago on Hugh Loebner and the Loebner prize. A madman it seems from the article. The concept of a Turing Test of an artificially intelligent machine (fooling an unknowing guinea pig into belieiving that the AI is real through conversation) will be known to many people. The Loebner prize is the embarrasing not-too-serious competion to actually run a Turing Test. The best machines entering get a 'best this year' award, but to actually claim the prize they have to actually fool a living person. The best machines are about as far from that as Leonardo da Vinci was from building an actual aeroplane.

Loebner, it turns out, is a rather strange person and fun to read about. The writer, John Sundman, is a little too happy to root for the little guy, against the establishment. In doing so he picks at several of my personal heroes (Marvin Minsky and Daniel Dennett) on what I consider completely unfair grounds. Both are accused of being establishment scientists locked up in dogma and absurd theory, and in these particular cases nothing could be further from the truth. Minsky and Dennett are to be commended for their extremely hands-on approach to doing science and philosophy respectively. Furthermore they have written very accessible books about their respective fields.

Minsky's society of mind is an extremely practical guess at some of the architectures that will be necessary to build actual intelligence of any kind. It is however not theory-free as Sundman and the infamous Richard Wallace (af A.L.I.C.E. fame - and quoted in the article) would like.

A.L.I.C.E will never win the Loebner prize - it just doesn't learn enough from the conversation even though one can seed it with very convincing replies.

Dennets consciousness book I haven't read. But 'Darwin's Dangerous Idea', while challenging reading is also one of the best books I have read in a while.

Sundman manages to give the impression that these are medievel progress hating nay sayers whereas they are in fact hardcore believers in manmade complex machines, call them intelligent or not.

The latest wired - a 10th anniversary issue seems to be flooding with old-style futurism. They're even bringing out that chestnut: Underground cities.

Having lived near Toronto I can testify to the fact (mentioned in the article) that this is already a reality there, which makes a lot of sense when it is unbearably cold on the upside.

There's only one little problem: Sunlight is still a much, much better source of light than any artificial source (in fact, here in Denmark it is illegal for a company to put their employees in offices without access to natural light) so either we have to dispense with that particular quality of life or somebody has to develop a good full-spectrum light source or these cities underground must be built with some kind of sunlight distribution system. Think parabolic ray collectors and fiber optic conduits - or maybe a collector up top and then a shaft with almost transparent mirrors reflecting low percentages of the intense light collected at every sub surface living layer it passes.

Another interesting thing about this is that real estate will become a three-dimensional, not a two-dimensional property. As far as I understand in Tokyo this is already the case. Due to the inflated prices of the eighties, legislation was passed limiting the right of property to some level underground, so that subways and other utilities could still be built during the boom.

The other important bit of futurism in todays Wired News is that the old dream of radio active physical objects. I'm not talking plutonium enriched milk, but rather products equipped with radio transmitters for identification. Ever since people first thought of the intelligent refrigerator (able to say "I'm out of cheese" to the supermarket service on its own) this has been a dream of many including Yours Truly - and of course an object of ridicule for even more people.

The first large scale application in the everyday world (i.e. outside industrial applications) is set to be Benetton clothing tags with RFID chips.

What's not so good about that is that the proximity of the clothes to your body means that they are effectively equipping you with a Radio Frequence ID chip - and that means that your Benetton store could soon be that annoying hyper personalized world that John Anderton tries to escape from in Minority Report.

However, until the IT-Department at Benetton screws up and publishes their customer database it is only Benetton who will be able to do that though, since the tag only identifies the garment. Indeed if well done it could simply provide opaque serial numbers and rely on alternate services to identify the specific garments a serial number refers to.

I think I'll coin a phrase to describe reactions to that experience : Identification Allergy.

This could soon be a very real and unpleasent experience (as failures in CRM systems and direct marketing has already made us intensely aware of)

But of course there are other problems to ponder first: What do washing instructions for silicon look like?

Wired news is awash with old style futurism (some of it near term) today. First off is an article from Wired 11.04: How Hydrogen Can Save America. This is an outline of how fuel cells could obsolete fossil fuels (think: Mass poverty on the Arabian Peninsula. No war with Iraq). There are some terrible costs of deployment of fuel-cell energy to replace the current fossil-energy infrastructure, but the prices are coming down, and the technology is (as promised so many times) almost there.

The article hasn't got much news. In fact I think the most significant news here is that the mere possibility of this technology has made ultra-green politicians in the worlds most technologically advanced state (that's California) force the major automakers to actually invest in this technology if they want a slice of this very rich market.

Surely we know that more people than an italian doctor will be willing to do human cloning, but there's a stretch from more people to The First Cloning Superpower, which might be China, as reported by Wired.

No surprise there, but it just goes to show that bioethics commitees shouldn't be used as oracles for legislative purposes. Decisions taken like that simply can't keep up with the science that is done, and forcing science to the pace of the committees would be a very bad idea.

The most wired piece I've seen in Wired for a while was in issue 10.11: A wonderful debunking of 'pop' technology books about the connectedness of the internet and information and all the wonderfull stuff that will appear out of this. The piece hilariously identifies all the common, overdone examples of connectedness and complexity (from amazonian butterflies to The Oracle of Bacon)The piece is pure graphics and translates poorly to the web.

Also in that issue is a debunking of a national report on progress in science and technology as a throw back to starry eyed 30s science fiction. I think it is a little unfair since even the overhyped technologies of nano and infotech do exist and progress has been made, even if it was also once a crazy dream.

Btw calling it

the best wired piece in a long time' is only in reference to the short graphic rich pieces. I think the magazine articles - if a little on the short side - have recovered quite well from the bubble greed that made the magazine be all about IPO's a few years back. That sucked. Starry eyed lame brained out there ideas are a wast improvement.

Every hacker watching The Matrix would know this: While the greenish glyphs streaming down the screen in the hacker submarine look really cool they do not represent in any significant way the use of visual information when hacking.

The reason: Our perception of visual information is geared for an enormous ability to orchestrate information spatially and this is done at the cost of a very poor visual resolution for temporal information.

We all know from the cinema what the approximate maximal resolution of visual information is : Approx 24 Hz, the rate of display for standard film. If it were better, movies would not look to us like fluent motion.

Our shape recognition ability on the other hand is almost unlimited and the brain even has some amazing computing related tricks where we have very high spatial resolution in the focus area of vision, which comes at the expense of general sensitivity (amateurs guess : Sincy you need a certain number of photons for a difference over space to be present you need a higher level of lighting to realize good spatial resolution). Our peripheral vision on the other hand is extremely sensitive, but has less resolution.

So a better way to construct a new age visual hacking device would be to keep the complicated glyphs - which we can easily learn to recognize - for focal vision and add peripheral information that is important but only as background information that may require us to shift our attention.

An idea for debugging could by glyphs representing various levels of function from the highest to the lowest - all visible at the same time - and then use the peripheral information for auxiliary windows. In the case of a debugger you could have variable watches etc. in the peripheral view and they would only flicker if some unexpected value was met.

I think complex glyphs would be a workable model for representing aspect oriented programming. In linguistic terms we would be moving from the standard indo-european model of language form to some of the standard cases of completely different grammers (insert technical term here) where meanings that are entire sentences in indo-european languages are represented as complex words through a complicated system of prefixing, postfixing and inflection. Matrix-like complex glyphs would be good carriers for this model of language.

Aspect oriented programming is reminiscent of this way of thinking of meaning, in that you add other aspects of meaning and interpretation of programming as modifiers to the standard imperative flow of programming languages. Design By Contract is another case in point. Every direct complex statement has a prefix and a postfix of contract material.

What would still be missing from the debugging process would be some sense of purpose of the code. And that's where the temporal aspects of hacking that the glyph flows in The Matrix represent come into play. A group of scientists have experimented with turning code into music. The ear, in contrast to the eye, has excellent temporal resolution in particular for temporal patterns, i.e. music. That's a nice concept. You want your code to have a certain flow. You want nested parentheses for instance and that could easily be represented as notes on a scale. While you need to adopt coding conventions to absorb this visually, failure to return to the base of the scale would be very clear to a human listener.

In fact, while our visual senses can consume a lot more information than our aural senses, the aural senses are much more emotional and through that emotion - known to us everyday in e.g. musical tension, the aural senses can be much more goal oriented than the visual. This would be a beautiful vision for sound as a programming resource.

They should make some changes in The Matrix Reloaded. The perfect futurist hackers workbench would consist of a largish number of screens. The center screens would present relatively static, slowly changing, beautiful complex images representing the state of the computing system at present. The periphery would have images more resembling static noise, with specific color flares representing notable changes in state away from the immediate focus. I.e. changes that require us to shift our attention.

While working, this code-immersed hacker would listen to delicate code-induced electronica and the development and tension in the code/music would of course be the tension in the film as well, and this then would tie the emotions of the hacker as observer of The Matrix - i.e. the software world within the world of the film - neatly to the emotions of the moviegoer.

No this is not an article about a failed 2M Invest company... Actual legislation is being proposed in the US Congress to allow any copyright holder to hack the hackersas reported on K5. In short, the proposed bill provides immunity for a number of possible liabilities caused by interfering with another party's computer, if the intent was explicitly - and upfront - to foil illegal use of copyrighted material.

This is the old "If guns are outlawed only outlaws will have guns" idea. Let the good guys give the bad guys a taste of their own medicine. Only, in the virtual world, where boundaries of location (especially in a P2P world) are abstract and hard to define, it seems to me that this bill is an extension of the right to self defence and the right to protect the sanctity of the home, to actually allowing aggresive vigilante incursions on other peoples property, when the other people are accused of copyright infringement.

It goes right to the core of current intellectual property debates, and raises in a very clear way the civil right issues involved in the constant and rapidly increasing attempts at limiting right-of-use for lawfully purchased intellectual property. Whose property IS intellectual property anyway?

UPDATED 20020731

In the olden days - when intellectual property was securely tied to some kind of totem, a physical stand-in for the intellectual property, in the form of the carrier of the information, i.e. a book or an LP or similar, there was a simple way to settle the issue. Possesion of the totem constituted an interminable right of use of the intellectual property. The only intellectual property available on a per-use basis was the movies. Live performance does not count in this regard, since live performance is tied to the presence of the performer, and the consumption of live performance is not therefore a transfer of an intellectual property to the consumer, in that it is neither copyable or transferable or repeatable.

It is of course the gestural similarity with live performance that has led to the rental model for film.

As the importance of the totem began to degrade, so began the attacks on the physical interpretation of intellectual property. We have seen these attacks and reinterpretations of purchase through the introduction of casette tapes, video tape, paper copiers, copyable CD rom media, and now just the pure digital file.

At each of these turning points attempts are made to limit the right-of-use to film-like terms. Use of intellectual property is really just witnessing of a performance. So you pay per impression, and not per posession.

What is interesting of late, and in relation to the lawsuit, is both the question of whether this 'artistic' pricing model is slowly being extended from the entertainment culture to all cultural interaction. Modern software licenses are moving towards a service-model with annual subscription fees. This could be seen as a step towards pure per-use fees for all consumable culture - an idea that is at least metaphorically consistent with the notion of the information grid. Information service (including the ability to interact) is an infrastructure service of modern society, provided by information utilities, and priced in the same way as electrical power.

In practice you do not own the utility endpoints in your home - the gasmeter and the electrical power connection to the grid. And ownership of any powercarrying of powerconsuming device does not constitute ownership of the power/energy carried or consumed. In the same way the content companies would have us think of hardware. And Microsoft would like you to think of Windows as content in this respect.

Secondly, there is the important question of how this interpretation of information and culture relates copyright to civil right.

The sanctity of physical space (i.e. the right of property) is a very clear and therefore very practical measure of freedom. Actions within the physical space are automatically protected through the protection of the physical space. There are very real and important differences between what is legal in the commons and what is legel in private space. And of course the most important additional freedom is the basic premise of total behavioural and mental freedom.

The content company view of intellectual property is a challenge to this basic notion of freedom. There is a fundamental distinction between the clear cut sanctity of a certain physical space, and the blurry concept of "use".

The act of use itself can be difficult to define, as property debates over "deep-linking" make clear.

In more practical terms, any use of digital data involves numerous acts of copying of the data. Which ones are the ones that are purchased, and which ones were merely technical circumstances of use. The legislation proposed enters this debate at the extreme content-provider biased end of the scale. Ownership of anything other than the intellectual rights to content are of lesser importance than the intellectual ownership.

The difficulty of these questions compromise the notion of single use and use-based pricing. And ultimately - as evidenced by the deep-link discussions - the later behaviour of the property user is also impacted by purchase of intellectual property according to the content sellers. This is a fundamental and important difference between the electrical grid and live performance on one hand, and intellectual property on the other. Intellectual property simply is not perishable, and, as if by magic, it appears when you talk about it.

Interestingly a person with a semiotics backgorund would probably be able to make the concept of "use" seem even more dubious, since the act of comprehension of any text or other intellectual content, is in fact a long running, never ending and many faceted process. In the simplest form, you would skirt an issue such as this, and go with something simple like "hours of direct personal exposure to content via some digital device". That works for simple kinds of use, but not for complicated use. And is should be clear from endless "fair use" discussions that content owners are very aware of the presence of ideas made available in their content in later acts of expression.

A wild farfetched guess would be that as we digitize our personal space more and more, expression will be carried to a greater and greater extent over digital devices, so that the act of thought is actually external, published and visible (witness the weblog phenomenon). In such a world, the notion that reference is use becomes quite oppresive.

Ultimately the concept of free thought and free expression is challenged by these notions of property. It is basically impossible to have free thought and free expression without free reference or at least some freedom of use of intellectual materials.

This whole humanistic intelligence thing is all fine and dandy - provided the new sensory experience of ever present communication impulses does not mean that we end up in an age of continuous partial attention. Neal Stephensons homepage (the link above) really does not want to be disturbed. His homepage is the longest single statement to the effect "Don't call me I'll call you" I have ever seen.

This entire thing about symbols/ideas/imagery reminds me of a talk I once heard the danish sculptor Hein Heinsen give. To put it briefly, Heinsen's approach to his work means there's a fundamental difference for him between sculpture and painting, in that the sculpture is a question of presence and being, whereas the painting is imagery and idea. As most everybody Heinsen believes there's a just too many ideas going around which of course becomes the grounding for working with sculpture. Of course the reality of it is that the sculpture as being is often a stand-in for some other 'real' being, so in fact merely the idea of being! Whereas the painting is often reduced from being an image to just being the traces of the imagining, so in fact more being. Heinsen claimed in all honesty that he was well aware of this flaw in his logic, and that his answer to the whole thing was to make very few sculptures! We should all have that luxury.

In simpler terms we can follow Stephenson and paraphrase

Donald Knuth: Email is a wonderful invention for people who want to be on top of things. I don't want to be on top of things. I want to be on the bottom of things.

Speaking of supercomputing, the connectivity of the brain compared to modern computer architectures is an interesting fact. Needless to say, this tells us that we have an insufficient understanding of the algorithms required for brain-like processing - but a more interesting question is whether the connectivity in itself adds a new complexity to the system that postpone the arrival time of brain-comparabel hardware. In other words, is the superscalar vector processing nature of modern supercomputers so decisive a simplification of the processing model that the hardware capacity of such a system simply is not comparable to brain capacity ? Among the questions implicitly asked: What is the memory/processing trade-off of the brain? What is the memory bandwidht?

Personally, I'm a technological optimist (we owe technology everything, and there's usually a technological fix). For those of opposite mind there's a lot of proof to be gotten from this list of 10 Technology Disasters. The link may require a (non-free) registration.